TFS Internals - How does TFS store Git repositories?

Git in TFS is just Git. Plain old vanilla git. Nothing fancy about it at all.

Well, almost. On the server, there is one significant change to be aware of. Files aren’t stored on the file system like they would be when git is running on your local machine. Instead they’re stored in the TFS SQL server database. Apart from that, it's the same as any other git server out there.

For a little fun I decided to dig into the TFS 2013 database to see just how the git files are stored.

NOTE: Don’t ever go hacking on your TFS databases. You’ll put your system into an unsupported state. All of the information that follows is a result of select statements only.

CAVEAT: The information here is based on me digging through the tables in the database. I’ve likely missed some items and may have made some bad assumptions. Feel free to leave a comment if you spot an error so I can correct the post.

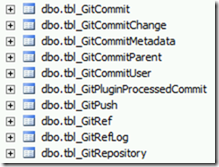

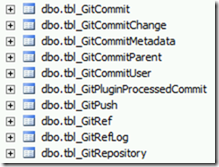

Firstly, looking through the tables in the TFS database we find a number of them are named tbl_Git*. This looks like a good place to start. Let’s see what they’re call and then what’s in them,

You’ll note there’s no ‘objects’ or ‘logs’ tables that might mirror the way a normal .git folder would look, though there is tbl_GitRef that might mirror the refs folder and that tbl_GitCommit table looks pretty interesting.

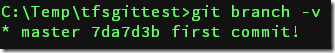

To figure out what ends up where, I made a new local repository, added a single commit to it, then pushed it to the git repository on TFS

Here’s what I found in each table:

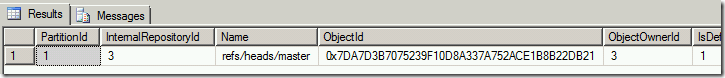

The InternalRepositoryId is used in other tables as part of their clustered indexes, avoiding the problems of using guids in indexes.

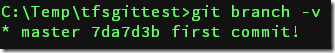

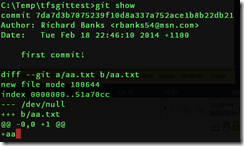

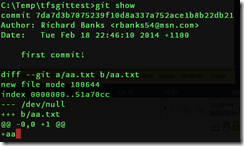

My local git commit was as follows:

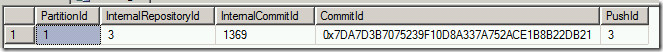

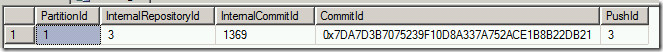

On the server we can see the commit’s SHA1 in this table with an InternalCommitId (unique across repositories by the looks of it) and what push it was related to.

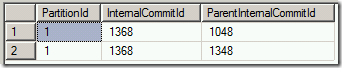

When you have merge commits, for example you will end up with multiple rows, as shown in this example. Note again the use of the internal ids instead of SHA1s to allow for clustered indexes on the tables.

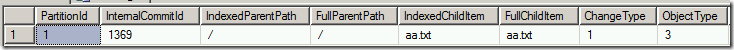

It’s indicating there was a file changed in the root of the git repo named aa.txt. Great. But where’s the content?

It turns out that TFS doesn’t hold the git content in a Git prefixed table, but somewhere else. There’s actually a few more tables in use, so let’s keep digging.

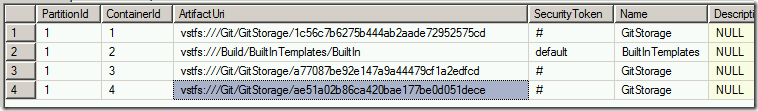

This ‘container’ URI is actually a reference to a location on the file system. Where? you might ask. Where indeed. If you look under the TFS Application Tier folder you will find a _tfs_data folder. Drill down past that to the Proxy folder and under that you will should find a folder with the same name as our repository’s GUID.

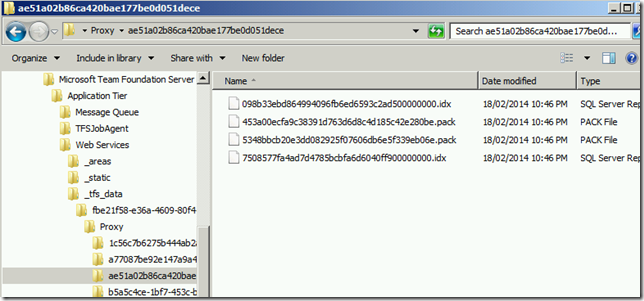

Look in there and you’ll find some interesting items, like those PACK files I’ve highlighted. These are your standard git PACK files. TFS is storing the data directly in the database but rather in the standard git pack format for efficiency. Interestingly the idx and pack files don’t share the same name as they would on a normal file system based git repo. I’m not sure why.

The statement that TFS stores the files on the file system is not entirely true. They’re probably there for performance reasons as if source was only stored on the file system, then the git content wouldn’t be backed up when SQL was backed up and that wouldn’t make people happy when they needed to restore a backup. So let’s see what else we can find.

OK. One last stop – where are these resources?

As for where the aa.txt file lives, well that’s going to be determined by git not TFS. Git will look at the index file and use that to decide where in the related pack file it should extract the content from. You’ll want to be looking into gits internals if you want to understand this process. See http://git-scm.com/book/en/Git-Internals-Packfiles for a good run through on this if you’re interested.

That’s about it for now. I think it’s pretty interesting to see how it all works under the hood and I hope you enjoyed the walkthrough.

Well, almost. On the server, there is one significant change to be aware of. Files aren’t stored on the file system like they would be when git is running on your local machine. Instead they’re stored in the TFS SQL server database. Apart from that, it's the same as any other git server out there.

For a little fun I decided to dig into the TFS 2013 database to see just how the git files are stored.

NOTE: Don’t ever go hacking on your TFS databases. You’ll put your system into an unsupported state. All of the information that follows is a result of select statements only.

CAVEAT: The information here is based on me digging through the tables in the database. I’ve likely missed some items and may have made some bad assumptions. Feel free to leave a comment if you spot an error so I can correct the post.

Firstly, looking through the tables in the TFS database we find a number of them are named tbl_Git*. This looks like a good place to start. Let’s see what they’re call and then what’s in them,

You’ll note there’s no ‘objects’ or ‘logs’ tables that might mirror the way a normal .git folder would look, though there is tbl_GitRef that might mirror the refs folder and that tbl_GitCommit table looks pretty interesting.

To figure out what ends up where, I made a new local repository, added a single commit to it, then pushed it to the git repository on TFS

Here’s what I found in each table:

tbl_GitRepository

As you’d expect on a server where you can have multiple repositories, this table just has a list of the repos that have been created. Repositories have partition ids and a Guid for the repository ID, but they also have an ‘InternalRepositoryId’The InternalRepositoryId is used in other tables as part of their clustered indexes, avoiding the problems of using guids in indexes.

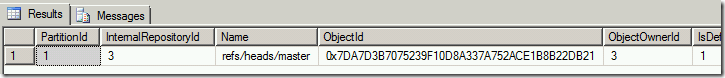

tbl_GitRef

This mimics the refs folder in a normal .git repo. You can see that the refs folder structure is tracked in the ref name and that the ObjectId matches my local repo.

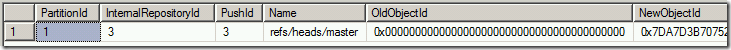

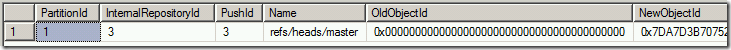

tbl_GitRefLog

This is as you might expect, a log of changes for the various refs. The thing to note here is that there is a pushId maintained in the table as well.

tbl_GitPush

Talking of push operations, tbl_GitPush is used purely to track the time of a push and who the person was who did it (via a Guid). Nothing much to see here, so let’s move on.tbl_GitPluginProcessedCommit

This looks to be a simple log of what jobs were executed against which commits.tbl_GitCommit

OK, so this one as it turns out is pretty straightforward. It’s a table of git commit SHA1’s mapped to internal commit ids.My local git commit was as follows:

On the server we can see the commit’s SHA1 in this table with an InternalCommitId (unique across repositories by the looks of it) and what push it was related to.

tbl_GitCommitMetadata

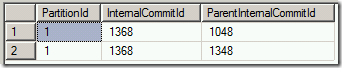

This table is for the commit comments and foreign key values for the committer and author.tbl_GitCommitParent

Since git tracks the parents of each commit, this table is used for that information. My example commit here has no parents so there’s nothing to show. The table itself only has three columns. The partition id, the InternalCommitId and a ParentInternalCommitId.When you have merge commits, for example you will end up with multiple rows, as shown in this example. Note again the use of the internal ids instead of SHA1s to allow for clustered indexes on the tables.

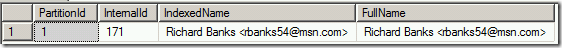

tbl_GitCommitUser

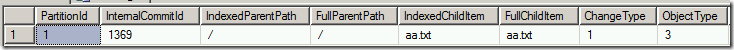

As alluded to before, this is simple a reference table of user InternalId values to names. Here’s my record for exampletbl_GitCommitChanges

So we’re on the last table with a git name. Looking at this for our commit we see the following

It’s indicating there was a file changed in the root of the git repo named aa.txt. Great. But where’s the content?

It turns out that TFS doesn’t hold the git content in a Git prefixed table, but somewhere else. There’s actually a few more tables in use, so let’s keep digging.

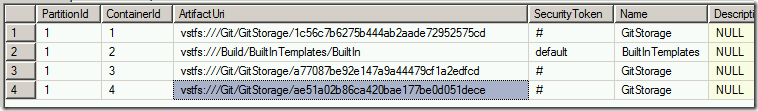

tbl_Container

Remember that GUID for the git repository we saw, right back at the start? We if we look at the container table we see that GUID referenced in an artifact URI on this table.

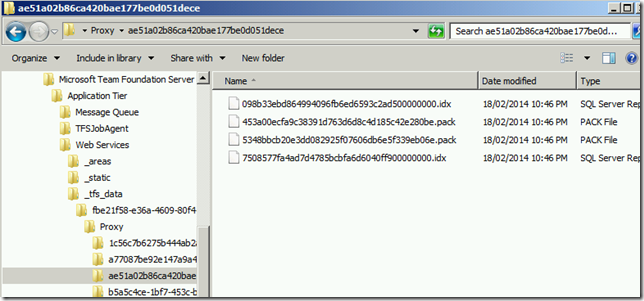

This ‘container’ URI is actually a reference to a location on the file system. Where? you might ask. Where indeed. If you look under the TFS Application Tier folder you will find a _tfs_data folder. Drill down past that to the Proxy folder and under that you will should find a folder with the same name as our repository’s GUID.

Look in there and you’ll find some interesting items, like those PACK files I’ve highlighted. These are your standard git PACK files. TFS is storing the data directly in the database but rather in the standard git pack format for efficiency. Interestingly the idx and pack files don’t share the same name as they would on a normal file system based git repo. I’m not sure why.

The statement that TFS stores the files on the file system is not entirely true. They’re probably there for performance reasons as if source was only stored on the file system, then the git content wouldn’t be backed up when SQL was backed up and that wouldn’t make people happy when they needed to restore a backup. So let’s see what else we can find.

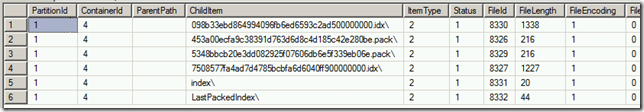

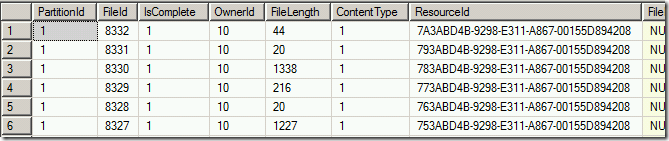

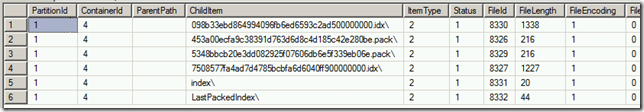

tbl_ContainerItem

If we select all items in the container item table we see the following. We can see the pack and index files we saw on the file system, but we also see that each has a file id and a file length.

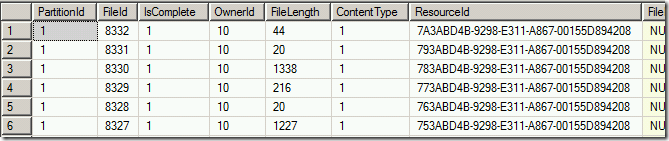

tbl_File

These fileids are part of the the tbl_File table which is effectively a mapping of a file id to a resource id.

OK. One last stop – where are these resources?

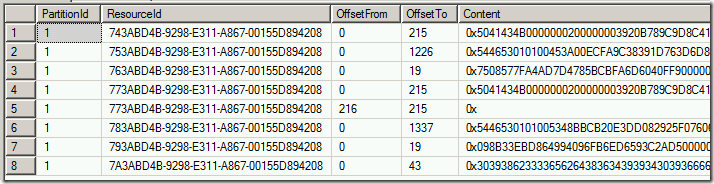

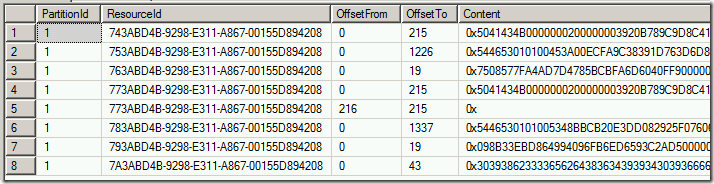

tbl_Content

Finally, we arrive at our destination. The Content column is a varbinary(max) column (i.e. blob storage) and contains our encoded content. Lovely!

As for where the aa.txt file lives, well that’s going to be determined by git not TFS. Git will look at the index file and use that to decide where in the related pack file it should extract the content from. You’ll want to be looking into gits internals if you want to understand this process. See http://git-scm.com/book/en/Git-Internals-Packfiles for a good run through on this if you’re interested.

That’s about it for now. I think it’s pretty interesting to see how it all works under the hood and I hope you enjoyed the walkthrough.